Things that stayed with me

Time flies a little faster with each year around the sun—making me appreciate the things that stand out and stay with me.

This past year was a big year for me: I graduated from my MFA program, got a new job, and “finished” my novel, which I’ve learned can be an elusive term when it comes to revising novels.

The thing with writing, reading, creativity, podcasts, hobbies, experiences—these blend in with the mesh of a 9-to-5 and daily chores. I want to claim I’m some type of purist with art in the sense of ingesting, producing, and appreciating art at all moments of my day, but that’s just not true. For many of us, that’s just not how life works. I’m not putting on three-hour dramas from cinephile top-100 lists after a long day of meetings. I’m putting on football.

All that being said, the things that stay with me take on an added sheen for this very reason. They stand out against the mundanity. They make an average life special. And I’m sure they’ve changed my life in minute—and, simultaneously, tremendous—ways.

Here are some things from my past year that stayed with me.

“Victim” by Andrew Boryga

When I came across Andrew’s journey, I was convinced my book—and writing—had no real place in the world. I had been in two MFAs, submitted to countless literary magazines, and fallen into an awful thought trap: why would an agent from Idaho, for example, give a fuck about a novel about a mixed Latino dude in New York chopping it up in Spanglish with his coro? Mind you, at that same time, I intuitively knew that good writing connects across backgrounds. I just couldn’t shake the attitude.

Right here, on Substack, I came across Andrew’s writing journey, and felt seen. I wrote to him as a reader with this same question of connecting. His response—and his writing—have fueled me ever since. (Link above.)

The day of Andrew’s reading in the Bronx, I dragged my friend down after work to accompany me. He’s not a writer or a literary fiction stan. He had come to chill with me. Then, the reading started. My friend locked in. He turned to me after Andrew read the last line: “I never thought I’d hear about someone like me in a book.” My friend and I started reading the next day and didn’t stop until we had finished.

Reading about Javier’s journey, watching his pops die in Puerto Rico, navigating his friendship with Gio after having “made it”—every note in VICTIM composed an incredible story of disentangling real life in America and the sacrifices of understanding class, ethnicity, place. Thank you, Andrew, for the writing the book that so many of us needed.

Tio Oscar

My uncle Oscar is a quiet guy, though he always seems to have these gems of wisdom to share with me when I come around. Maybe that’s just the uncle way—something I’ll have to practice for when my niece grows up.

He’s worked as a taxi driver my whole life, putting aside a few coins to support his family, making sure to always have a warm welcome ready for me when I visit (read: huge pot of arroz con mariscos). He’s the type of person I’ve tried to capture in my writing so many times, only to fall short. That’s the challenge, I think, of great writing—to encapsulate even a tiny bit of that humanity that makes our own lives shine.

To him, writing fiction might seem like an odd pursuit—or illogical one, better put. My family in Panama has shared this attitude in general ever since I visited while in college and shared that I was an English Lit major in college. Like, really? English Literature? When you could study engineering, medicine, or law? That said, my uncle has always supported me and accepted my inclinations.

This past year, I faced challenges in work, and aspirations of growing in my field, and I thought back to a moment with my uncle. I had shared about withdrawing a bit from work so as to maintain more distance from it, personally; the idea, in my mind, was to lessen the stakes by making myself less invested.

He pushed back. “This is your time,” he said, referring to youth. “You have to work hard. You have to work for what you want. Hay que seguir dandole. Don’t let up.” I run through that moment again and again when I think of chasing my dreams.

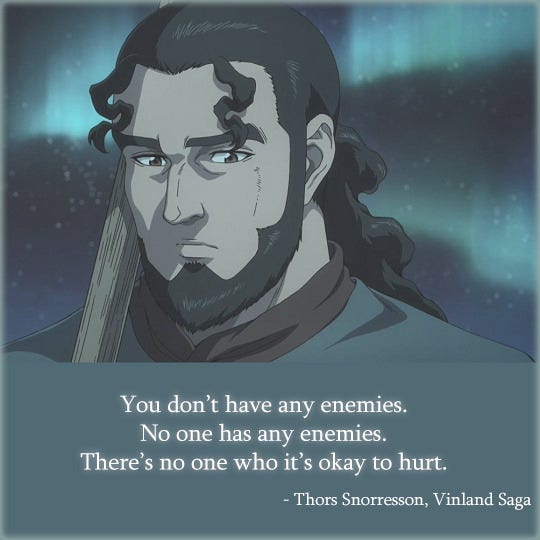

Vinland Saga

Looking back, this anime had the perfect recipe to connect to someone like me: the son of Thors, Thorfinn, dedicates his life to revenge after witnessing his father’s death. His father, however, a legendary war hero, combatted this very line of thinking, sharing the famous quote above. Later in the show, Thorfinn embraces this concept, even pushing the idea of peace and non-violence amid urgent calls to protect his loved ones.

My father served in the military for 32 years. I’ve dedicated much of my life to critically engaging with the principles that I think I’ve absorbed from the military. Since America has always maintained a “flavor of the week” when it comes to enemies, how has this reflected in how we view others? Do we arm ourselves with visions of imaginary “enemies” with the hopes of highlighting our own identities? Do we hope for calls of revenge as a way of charging our lives with meaning?

No spoilers, but at the end of this show, Thorfinn tries to imagine a world in which peace prevails, in which the respect for human life precludes violence. He’s inspired by a fallen friend who called into question the need to survive after sustaining major injuries: “why do I need to survive? What’s so special about life?” This scene moved me deeply in wondering how we could envision kindness and respect as principles to our world, or how we could highlight the beauty of life.

“Behind You is the Sea” by Susan Muaddi Darraj

I won’t be able to capture what’s so deeply moving about this book, other than a quality that it shares with “Victim”: it’s real. It’s real life in wrestling with class, race, power, education, home, family.

This book is an interconnected series of short stories that revolve around a Palestinian family in Baltimore. As children of this family grow up and form their own families, we follow the tributaries of immigration in America: the one do-good child who maintains perfection in her professional life, assuming the “breadwinner” role; the bright scholar who ruins her reputation in her family for dating a Black man; the hard-nosed cop, embracing American ideals, assimilating, only to have his ideals tested when he revisits Palestine to bury his father.

The more I write, the more I find value in the idea of realistic portrayal in its own right: not experimental craft, like stream of consciousness, but our more traditional craft techniques that help compose meaningful stories that bring us back to why we read—the humanity in others, the sense of place, the test of life. It’s hard. It’s really hard. Reading this book, I almost wonder how it hasn’t been written before—it feels so deeply familiar, such a true testament to life in this family, to the American experience. Perhaps that speaks to this book’s strength in seamlessly enveloping the reader in a new, yet familiar, world.

Bonus: “Cosa Nuestra” by Rauw Alejandro

“Esto es lo que quieren, toma reggaeton”—NORE

No big surprise, but reggaeton has played a huge role in my life since I first started really listening as a teenager. It has connected me and friends and cultures. It has grounded me in my own culture. It serves as a motif in my novel, which I hope sheds light on why it matters so much to Latinos like me.

I think to others, it all kind of sounds the same: boom, boom-ch-boom-chick.

But albums like Rauw Alejandro’s “Cosa Nuestra,” which came out this past November, speak to its inventiveness. He uses “Cosa Nuestra” and reggaeton as base points for expressing himself in a boldly unique way—while also paying homage to his roots. He’s got salsa on there, Latin trap, pop beats, everything you need. I like to think of myself as the same: forging ahead in creating art that so distinctly captures me while refusing to shy away from the parts of me that I can’t change: my Uncle Oscar, my military background, my distinct worldview.

Thanks for sharing in some of this journey this year.